Reclaiming my Deaf Lineage

I did not meet my grandfather’s brother, Isidore Dietz, until we sat Shiva at my grandparent’s house n 1983. He was the splitting image of my grandfather, and I was shocked and inconsolable when we met. He was Deaf and he signed, and his wife, Celia, signed back and was able to hear and speak with me. That was the only time that I saw him or even spoke about him, and I did not think about him for years until I read Jennifer Natalya Fink’s essay in the New York Times, We Should Claim Our Disabled Ancestors With Pride.

Given that roughly one in four adults have a disability of some kind, all our families include disabled ancestors. Disability is part of every family story. But we have to know of our disabled kin to claim them.

It is important to recognize and understand our ancestors and the struggles that they may have had as being part of a minority population that has been stigmatized and hidden in the shadows of family trees. By reclaiming and retelling our family stories and including, and being proud, of what they had to go through, whether they were queer, disabled or otherwise marginalized, like putting a stone on their headstone, it honors their lives and blesses their memory.

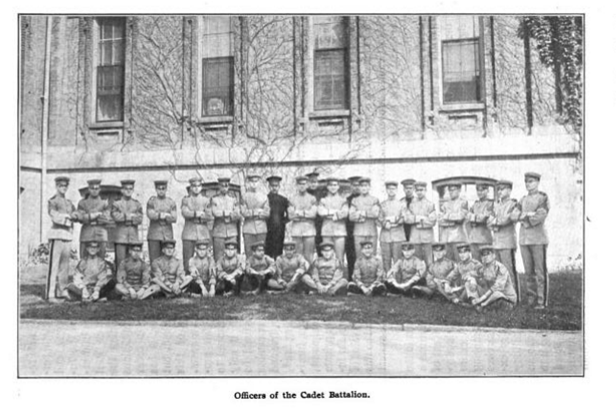

So back to Isidore. I typed in his name in Google Books and I found the 1921 and 1922 reports from the New York Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb. It was located in Washington Heights in New York City, where the campus of the Columbia University Medical School is now located. Isidore is one of the boys in the picture below:

The institution was co-educational, and for the boys – the first military school for the Deaf. However, these boys would never be allowed in the military, as people who were deaf could not be in the military since the Civil War. In 1881, the Institution was proud to switch to a fully oral instruction for the students. Some of their staff went to the Second International Congress on the Education of the Deaf in Milan. After this conference, the New York Institution wanted to be declaration was made that oral education was better than manual (sign) education. As a result, sign language in schools for the Deaf was banned.

I could not imagine how life was in that institution for a teenager. Was corporal punishment inflicted on Isidore when he attempted to sign and communicate with his fellow students? Did he resent his brothers who were able to be home with his parents and play with his friends when he was required to go through a regimented life in an institution? Could he communicate with his family? Was he an adult when he learned ASL? Did he dread going to a family event where his family did not know him at his brother’s Shiva, and did any extended family members attend his Shiva in Florida?

For the past twenty years litigating cases regarding effective communication and inclusion for the Deaf Community, I never realized that I had a deeper, personal connection to the work that I do, and embarrassed at how Isadore was treated. I wonder if any of my clients knew him and made the connection.