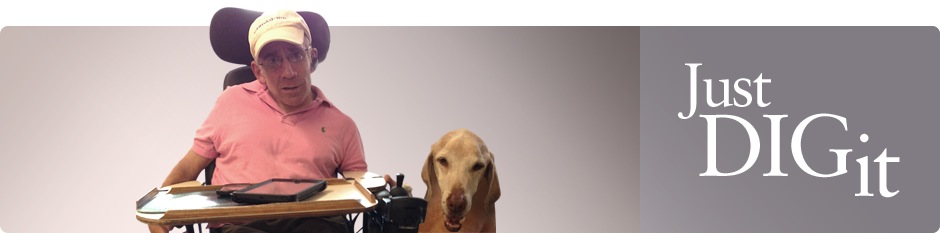

Fear should not be a barrier to full community integration

By: Matthew Dietz

On August 18, 2015, Carl Starke, an Autistic man, was shot by three teenagers who were casing the Wal-Mart parking lot for cars to steal; they spotted Carl in the parking lot, and followed him home. They somehow noticed that he had a disability – he was marked as a “soft target”. The plan was to steal his car, but when he arrived home at the condominium development where he lived with his mother, they shot him dead.

This week, the Florida Legislature is considering renaming a particular section of the hate-crime law to “Carl’s Law” to memorialize Carl Starke. According to Rep. Cyndi Stevenson (R-St. Johns) the law is being changed —to honor Carl’s life and build awareness of Florida’s increased penalties for crimes committed against people with disabilities to help prevent future tragedies.

House Bill 387, as drafted, is well meaning, but, it merely removes provisions on disability-based hate crimes from Florida’s existing hate crimes law – §775.085 – and inserts this language into a new statutory provision. Disability Independence Group is opposing this bill because it fails to protect persons with disabilities and it continues time-worn stereotypes that persons with disabilities are all “incapacitated.”

As reflected by state and federal crime statistics, far too few crimes against the disabled are classified and investigated as hate crimes. From 2002 to 2013, the Florida Attorney General reported a total of 1,319 hate crimes in the State of Florida, but only three of these crimes were based on disability. However, U.S Department of Justice statistics demonstrate that persons with disabilities are more than twice as likely to be victims of violent crime compared to persons without disabilities From 2008-2013, persons with disabilities experienced 1.3 million violent victimizations, which accounted for 21% of all violent victimizations. Part of the discrepancy is the definition of “disability” under the Florida hate crime law, as follows:

the term “mental or physical disability” means a condition of mental or physical incapacitation due to a developmental disability, organic brain damage, or mental illness, and one or more mental or physical limitations that restrict a person’s ability to perform the normal activities of daily living.

This definition would not include Carl Starke. From all reports, Carl Starke, like most persons with disabilities, was far from incapacitated. Carl had a large and supportive network of family and friends in the Jacksonville area. He worked for years at Publix Super Market, and then worked Republic Waste Management as a loader. Carl made daily trips to Game Stop, Home Depot and Wal-Mart, and made friends wherever he went. Carl loved college football and spending time with his family and friends. He enjoyed working on his car and tinkering with various projects. According to Carli Durden, his sister:

“We were lucky to have him for 36 years. We wish everyone could have a Carl in their family,” Durden said. “Carl was autistic but functioned in the highest capacity. He was very special to us and was never treated any differently. His autism was considered a gift to us, and that is what made him our Carl.”

This bill has no effect on providing law enforcement with the tools it needs to investigate and prosecute more hate crimes against persons with disabilities. Increasing investigation and prosecution of bias crimes against persons with disabilities requires substantive changes to Florida’s hate crimes law.

According to 2010 U.S. Census Data, out of the 56.7 million persons with disabilities in the United States, less than two percent have an intellectual or developmental disability. Further, many persons with Autism or other developmental disabilities are fully able to be involved in many, if not all, aspects of society, and make decisions on their own. As such, these persons are not, in any sense of the word, incapacitated. The millions of persons who are have physical disabilities, visual or hearing disabilities may similarly be “soft targets.” Hate crimes demand priority attention because of their special impact. They intimidate the victim and members of the victim’s community, leaving them feeling isolated, vulnerable, and unprotected by the law. With more and more persons with disabilities integrated into the community, vigorous investigation and prosecution of hate crimes against persons with disabilities sends the powerful societal message that persons with disabilities should not have fear as a barrier to full community integration.

Disability Independence Group has joined the Florida Hate Crimes Coalition to attempt to urge the sponsors of this bill to amend it to update the hate crime’s law definition to include all persons that have disabilities as in the Florida civil rights law, and not segregating persons with disabilities from all persons that are protected by the Florida Hate Crimes Act.

Notes:

- The information about the life and tragic death of Carl Starke was obtained through news reports and his obituary.

- The Florida Hate Crimes Coalition is comprised of the Anti-Defamation League, Autistic Self Advocacy Network, Center for Independent Living of South Florida, Coalition for Independent Living Options, Disability Independence Group, Emerge U.S.A., Florida Association of the Deaf, Hadassah Florida Central, National Council of Jewish Women, The Deaf Service Center Association, Inc. of Florida